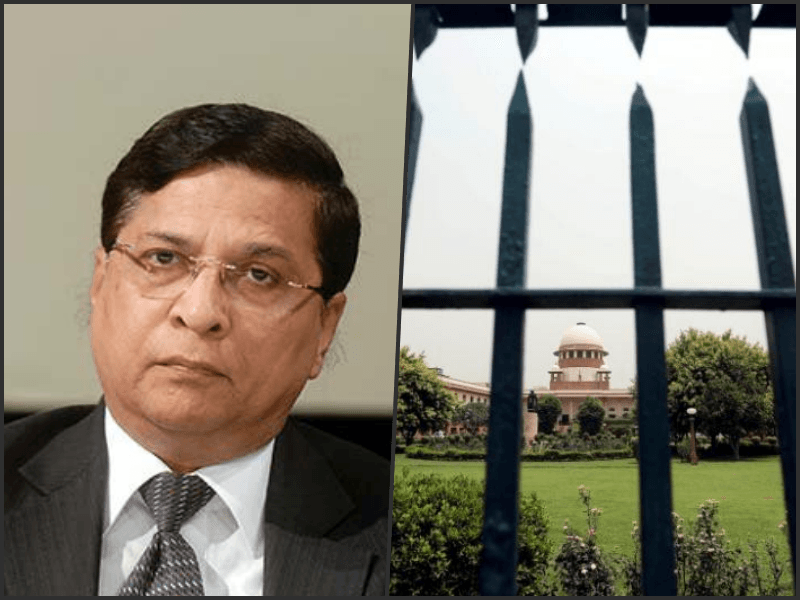

Should a Judge With a Serious Moral Flaw Become Chief Justice of India? – BY Shanti Bhushan

On August 27, Chief Justice of India (CJI) J.S. Khehar will demit office. The next in line is Justice Dipak Misra, but should the vacancy be filled up simply by the rule of seniority? The CJI

On August 27, Chief Justice of India (CJI) J.S. Khehar will demit office. The next in line is Justice Dipak Misra, but should the vacancy be filled up simply by the rule of seniority?

The CJI is a constitutional authority and presides over the country’s judiciary, comprising 31 Supreme Court justices, over 1000 high court judges and over 16,000 subordinate judges. The CJI dispenses justice in the highest court in cases involving complex constitutional issues, issues affecting the rule of law, issues having an impact on governance in the country, issues touching the lives and liberties of 1.3 billion Indians, and dispenses justice in regular civil and criminal appeals. As head of the Supreme Court, the CJI wields wide powers not just in administration but also in constituting benches and allocating matters, often politically sensitive ones.

In the First Judges case, the Supreme Court emphasised:

“Judges should be of stern stuff and tough fibre, unbending before power, economic or political, and they must uphold the core principle of the rule of law…”

In the Second Judges case, the Supreme Court in 1993 held:

“It is well-known that the appointment of superior judges is from amongst persons of mature age with known background and reputation in the legal profession… The collective wisdom of the constitutional functionaries involved in the process of appointing superior judges is expected to ensure that persons of unimpeachable integrity alone are appointed to these high offices and no doubtful persons gain entry. It is, therefore, time that all the constitutional functionaries involved in the process of appointment of superior judges should be fully alive to the serious implications of their constitutional obligation and be zealous in its discharge in order to ensure that no doubtful appointment can be made.”

The Supreme Court thus gave primacy to the CJI in the process of selecting judges to be appointed to the apex and high courts. The CJI thus wields enormous power in shaping the future of the judiciary. That is why the present CJI in the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) case has warned:

“The sensitivity of selecting judges is so enormous and the consequences of making inappropriate appointments so dangerous that if those involved in the process of selection and appointment of judges to the higher judiciary make wrongful selection it may well lead the nation into a chaos of sorts.”

In Manoj Narula vs Union of India, Justice Misra himself observed, “A democratic polity, as understood in its quintessential purity, is conceptually abhorrent to corruption and, especially corruption at high places.”

Land allotment case

Yet, Justice Misra has surprised many by what appears to be a serious lapse in conduct. He had applied for and obtained a lease of two acres of agricultural land in 1979 (while he was a lawyer) from the government of Odisha. In the affidavit filed by him (as a condition for allotment) he said: “I am Brahmin by caste and the extent of landed property held by me including all the members of my family is nil.”

The lease was later cancelled by a well-considered order passed against him by the additional district magistrate of Cuttack on February 11, 1985, in proceedings under the Orissa Government Land Settlement Act, 1962:

“This G.O specifically provides vide paragraph 4 that a landless person is one who and his family members do not hold land more than two acres and who have no profitable means of livelihood other than agriculture… Therefore I am satisfied that the opposite party (Justice Misra) was not a landless person and as such he was not eligible for settlement of govt land for agricultural purpose. On this ground alone, the lease is liable to be cancelled… I am satisfied that the lessee has obtained lease by misrepresentation and fraud.”

It also appears that there were many other persons who had claimed such land by questionable means. In a writ petition filed by Chittaranjan Mohanty in the high court of Odisha, the court had passed an order on January 18, 2012, directing the CBI to enquire and investigate into unauthorised encroachment/occupation of government lands in the said area. The CBI had registered preliminary enquiry stating:

“(a) PE 1(S)/2011 for probing into the alleged unauthorized encroachment of entire Government land at Bidanasi Area of Cuttack District comprising of 13 mouzas viz Bidyadharpur, Bentakarpada, Ramgarh, Thangarhuda, Brajabiharipur and Unit 1 to Unit 8.”

The CBI submitted a final status report on May 30, 2013, wherein it expressly found that:

“In this case, Shri Dipak Mishra, S/o Raghunath Mishra, Vill-Tulsipur, PS- Lalbagh, Cuttack & permanent R/o Banpur, Puri was sanctioned 2 acres of land by the then Tahasildar Mr. J. A. Khan on 30.11.1979 at Plot No 34, Khata No 330, Mouja- Bidhyasharpur.”

“The allotment order of Tahasildar was cancelled by ADM Cuttack vide Order 11.02.1985. But the record was corrected only on 06.01.12 as per the order passed by the Tahasildar, Cuttack only after 06.01.2012.”

The CBI further found that:

“Enquiry has already revealed certain instances of irregular leasing out of government land to ineligible beneficiaries by the Tahasildar, Cuttack Sadar during the period 1977 to 1980 in Bidyadharpur Mouza. Though some of the cases of irregular lease were cancelled by the ADM (Revenue) on review but the leaseholders had not vacated the said land. Even the records were corrected after 06.01.2012 even though the lease was cancelled during 1984-85.”

The fate of the high court proceedings subsequent to this report remain unclear.

A false statement made in declaration, which is by law receivable as evidence, and using as true such declaration knowing it to be false, are serious offences under Section 199 and Section 200 of the IPC, punishable with up to seven years of imprisonment and a fine. The filing of that affidavit by Justice Misra is thus a very serious matter.

Justice Misra’s name has even appeared in the suicide note by former Arunachal Pradesh chief minister Kalikho Pul. Though no investigation has taken place in that matter, the inquest report found the suicide note to be genuine. Under Section 32 of The Evidence Act, a suicide note has evidentiary value and must be followed up with a detailed enquiry after lodging an FIR, if need be.

Recently, newspaper reports have also appeared about Justice Misra’s name cropping up in the course of an enquiry by three judges of high courts into allegations against two sitting judges of the Odisha high court.

Should such a person become the CJI, even if he is the senior-most judge? Seniority is an important principle, though not the only principle for appointing the CJI. I have always opposed the supersession of judges for political or ideological considerations. As law minister in 1977, I had opposed the strident demand from my party to supercede judges who had decided the infamous habeas corpus judgement during the Emergency. In this case, however, the issue is of unsuitability on serious ethical considerations.

The recommendation by the present CJI for Justice Misra to succeed him is unfortunate in light of his own observations in the NJAC case. The country will now have to look up to the president and the prime minister to perform their duties, send back the CJI’s recommendation and suggest the appointment of the next judge in seniority.

Shanti Bhushan was India’s law minister from 1977-79 and is a senior advocate in the Supreme Court.