Justice Chelameswar Retires From SC But Leaves Behind Fine Legacy

VISHNU GOPINATHVAKASHA SACHDEV 2018 has been an interesting year for the Indian judiciary. The third pillar of Indian democracy, the one tasked with protecting and preserving the rights of Indian citizens, has had a decidedly tumultuous

VISHNU GOPINATHVAKASHA SACHDEV

2018 has been an interesting year for the Indian judiciary. The third pillar of Indian democracy, the one tasked with protecting and preserving the rights of Indian citizens, has had a decidedly tumultuous year. And one name that has figured prominently in much of the debate around the current state of affairs is Justice Jasti Chelameswar, the second-most senior judge of the Indian Supreme Court, after Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra.

Justice Chelameswar is the second of the five most senior judges of the Supreme Court who form a part of the Supreme Court’s Collegium, the body tasked with appointing judges to the High Court and Supreme Courts

He will retire as a judge of the Supreme Court on 22 June. However, since the courts will soon shut for the summer, Justice Chelameswar’s last day of work, effectively, is 18 May. Unlike many other Supreme Court judges, Justice Chelameshwar has said, in no uncertain terms, that he will not be taking any job from Central or State Governments after his retirement.

His seven-year tenure, beginning in 2011, has seen some of the most polarising moments in the history of the Indian judiciary, from his contrarian stand in the NJAC ruling, to the Judges’ Press Conference on 12 January 2018.

Before the man referred to as the “flag-bearer of dissent” retires, and hangs up his robes one last time, we take a look at the highlights of Justice Chelameshar’s seven-year Supreme Court tenure.

The NJAC Verdict

The National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC) Act was passed in 2014, in an attempt to change the existing Collegium system of appointment of judges. The Act sought to form a Commission with members suggested by the Government and the opposition, along with members the judicial fraternity, in an effort to ensure the judiciary didn’t have final say in the appointment of judges. The Act, and the amendments to the Constitution to enable its implementation were deemed unconstitutional by a five-judge bench of the SC in 2015, by a vote of 4:1.

Chelameswar was the sole voice of dissent on the Bench. He voiced his concerns against the existing Collegium system, and in support of the NJAC Act, stating that transparency was a vital factor for Constitutional Governance, adding that:

Proceedings of the collegium were absolutely opaque and inaccessible both to public and history, barring occasional leaks.Chelameswar, in his ratio for giving the contrarian verdict, added that:

To hold that it (the government) should be totally excluded from the process of appointing judges would be wholly illogical and inconsistent with the foundations of the theory of democracy and a doctrinal heresy.Despite these being his views, Justice Chelameswar accepted the majority judgment, and in fact subsequently championed the cause of the judiciary against government interference – even calling out judges whose decisions undermined the Collegium’s position on the Memorandum of Procedure for appointing judges.

At the same time, he has continued to advocate for necessary reforms and transparency, and was instrumental in the Collegium’s decision to make its resolutions public in January 2017.

Section 66A, Aadhaar and The Privacy Debate

In 2015, a division bench of Justice Rohinton Nariman and Justice Chelameshwar, in the case of Shreya Singhal vs Union of India, struck down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act as unconstitutional and violative of the fundamental right to free speech and expression under Article 19 of the Constitution. The reasoning laid down by the bench was:

…the possibility of Section 66A being applied for purposes not sanctioned by the Constitution cannot be ruled out. It must, therefore, be held to be wholly unconstitutional and void.

Section 66A had been used to censor and threaten people from all walks of life for the most flimsy reasons, whether expressing political dissent or just making fun of someone with influence. Striking it down went a long way towards ensuring that the right to freedom of speech and expression was not curtailed by dubious means.

This would eventually have consequences in the debate over the right to privacy in India. As the judge presiding over the Aadhaar hearings in 2015, Justice Chelameswar was the one who referred the case to a Constitution Bench to decide the question of whether privacy was a fundamental right, after the Central Government had tried to argue that there was no such right under the Constitution.

Despite referring the matter, Justice Chelameswar did order that linking of Aadhaar to various services could not be made mandatory. The Centre eventually tried to get around this by arguing that the stays no longer applied after the Aadhaar Act 2016, but Justice Chelameswar had at least provided a basis to stop the rampant spread of Aadhaar at a point when it was, in effect, unregulated.

He would subsequently author one of the opinions in the landmark privacy judgment, holding that privacy was in fact a fundamental right, and was an essential aspect of liberty and dignity.

The Judges’ Press Conference

The press conference called by the four judges of the Collegium, save CJI Dipak Misra, on 12 January, was the first time in the history of the Indian Judiciary that sitting judges of the Supreme Court addressed the media about their concerns surrounding the Apex Court’s functioning, as well as publicly questioning the allotment of cases of significant legal questions by the head the Collegium, Chief Justice Dipak Misra.

“Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra has left us with no option but to go public about what is going on within the collegium,” the four senior judges of the apex court said. They alleged that that the “administration of the SC is not in order.”

Justice Chelameswar, at whose residence the press conference was held, along with Justices Ranjan Gogoi, Justice Madan Lokur and Justice Kurian Joseph, said:

Judicial independence is key to the survival of democracy. I don’t want some wise men to say that Justices Chelameswar, Lokur and Joseph sold their souls and did not take care of the institution. We just wanted to communicate this to the nation.

The four judges, led by Chelameswar, also released a letter alleging preferential allotment of cases, especially those with large-scale significance, alleging that benches had been appointed to cases without any specific reasoning. The letter had been written to CJI Misra back in November 2017, and only released after repeated efforts by the senior judges to have their concerns addressed by the Chief Justice had failed.

This was a bold move fraught with risk for the judges, as it went against all past precedent, and would open them up to allegations of impropriety and vendettas. Through it all, Justice Chelameswar continued to maintain propriety, asserting that their problems were not entirely of CJI Misra’s making, and had been problems in the Court even before him, refusing to resort to mud-slinging.

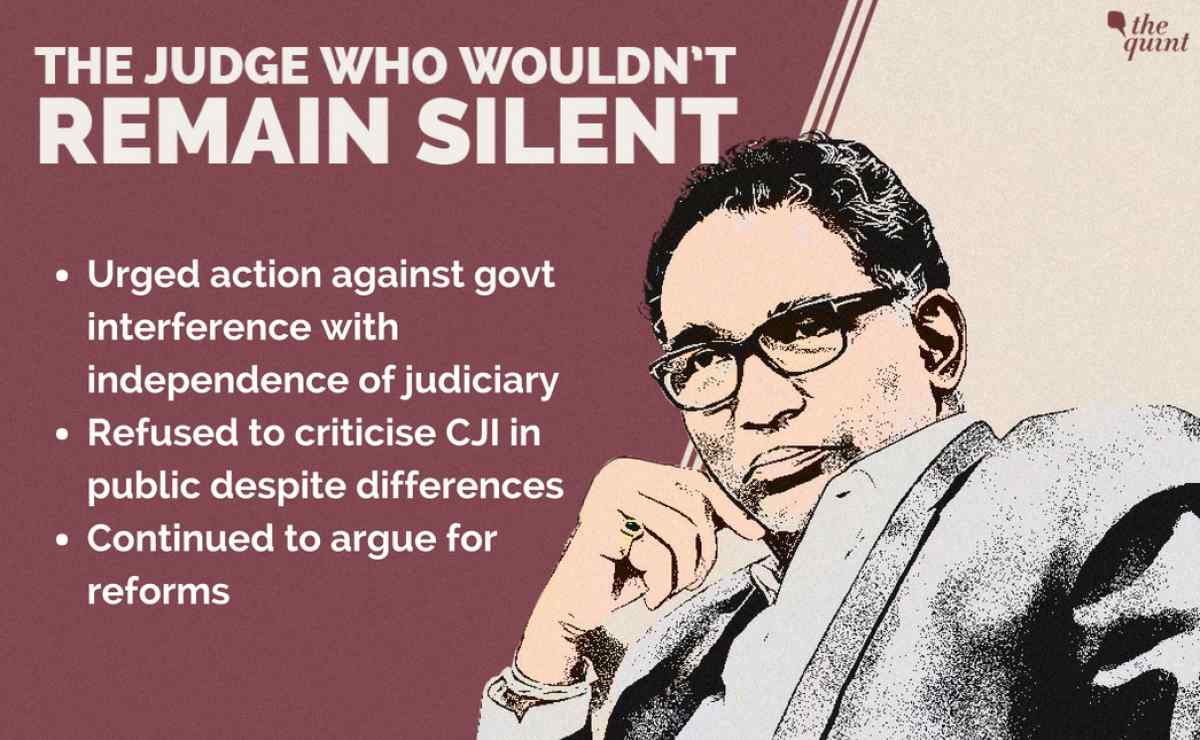

The Judge Who Refused to Remain Silent

The Press Conference would have consequences for the four judges, with the CJI’s new roster system excluding them from hearing any PILs – including all the big-ticket issues such as the Aadhaar case, the challenge against Section 377 of the IPC, and others. Despite this, Justice Chelameswar at no point criticised CJI Misra in public.

At the same time, he continued to talk about the things he felt were important, and did not refrain from urging reforms that he thought necessary for the judiciary. In a conversation with Karan Thapar, he explained how selective allocation of cases created doubts in the minds of people, which was dangerous for an institution like the Supreme Court, and why this was something he felt was necessary to speak up against.

Undoubtedly the Chief Justice would have the authority to constitute the benches. But under a constitutional system, every power is coupled with certain responsibilities. The power is required to be exercised not merely because the power exists, but for the purpose of achieving some public good.This was a remarkably measured response, since the CJI had asserted this power in November 2017 to reverse a decision by Justice Chelameswar and insist the CJI had the power to decide which judges would hear cases, even if the case involved allegations against the CJI. In fact, when the impeachment charges were raised against the CJI, Justice Chelameswar instead insisted that impeachment wasn’t the correct way to go, eschewing an easy opportunity to criticise the CJI.

At the same time, he refused to remain silent on issues which he felt the CJI wasn’t doing enough about, writing letters to him urging action against government interference and sabotage. These included concerns over the Centre’s attempts to bypass the Supreme Court and investigate Karnataka judge P Krishna Bhat, and the lack of response on the Collegium’s recommendation to appoint Justice KM Joseph to the apex court.

At other public events including book launches, he also urged reforms to the way the Supreme Court operated to reduce pendency, including appointing more judges, and fighting backlog.

Through everything, Justice Chelameswar has stood up for his principles, and acted with integrity and to ensure the judiciary properly fulfils the essential role it must in a democracy. His philosophy can perhaps be best summed up in his own words:

“I always believed that there is a great way of doing small things, and there is a small way of doing great things.”

Whether dealing with great or small things, the way he has conducted himself over the last seven years and the last few months in particular, mean he will leave behind a legacy of dignified dissent and unassuming rectitude. We can only hope everything he has done and stood for will not be in vain.

(The Quint is now on WhatsApp. To receive handpicked stories on topics you care about, subscribe to our WhatsApp services. Just go toTheQuint.com/WhatsApp and hit Send.)

https://www.thequint.com/news/india/justice-chelameswar-retires-supreme-court-legacy-dissent-njac-press-conference